About a week ago, I noticed there was a purple film on the sides and bottom of my vinyl swimming pool. My first thought was, “Could this be a weird, new algae?” I have had trouble with algae a couple of times over the last fall and winter, mostly because I got behind with measuring and adding the swimming pool chemicals due to life events. However, those algaes had been a boring translucent white. A little step up in my attention to the pool chemicals had dealt with the problem, and I didn’t even have to stop swimming.

The pH had been on the low side for a few months, too, and I had learned that that could make the chlorine less effective, so was adding my baking soda regularly to try to raise the pH. Sometimes it would almost get up to the optimum 7.2, but it would never stay. It was explained to me that this was why the chlorine was getting used up faster, too. However, with the water clear, I wasn’t terribly concerned. Until my pool started to turn deep purple.

It turns out that the low pH (mine was consistently 6.8 – 6.9, even with all the baking soda I was adding) creates a chemical environment that stimulates the corrosion of the copper in the swimming pool heater. I was strongly encouraged to add much more baking soda over the next couple of days to keep this from happening more. Apparently, if the pH got lower, the copper in a brand new heater could get holes in it in less than a month. Our heater is almost 2 years old.

I got right home and put my first extra dose of baking soda in the swimming pool, went for a swim, and had lunch. While I was eating, I did some research on this corrosive pool chemistry to try to better understand. I found this interesting article explaining swimming pool chemistry in more standard chemical terms. The standard terms meant I could compare it to other things I knew about chemistry. More importantly, I could look up things about the chemistry in general resources, instead of just relying on the literature of pool chemical companies. I learned two important things.

1. I had thought that all I had to do was get the pH up and it would stay. This assumption was partly based on the fact that I had absolutely no trouble with my pH for the first few months. Turns out this is not the case, especially if using the hard disk, slow-dissolve chlorine. These disks, or pucks as referred to in the above article, are in the form of trichloroisocyanuric acid. Notice the word “acid” on the end of that description. Basically, by using this form of chlorine, I am constantly lowering the pH in my swimming pool, so need to be constantly adding baking soda. I thought I was adding a lot, but it wasn’t enough.

2. Measuring the alkalinity is really all about measuring a specific base, the hydrogen carbonate ion. This is what I am adding when I put in baking soda, also known as sodium bicarbonate. When my alkalinity is low, I need to add more of it, but it does take a while to mix well and get a good reading, so this increases the need to check on it regularly to not let it drop.

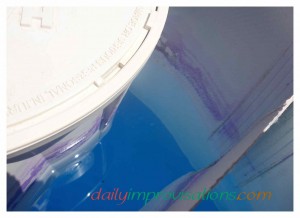

When the swimming pool looked purple, there was not anything obvious floating in the water, like with the algae. The precipitate from the corrosive reaction seemed to stick loosely to the vinyl. This purple residue was easy to brush off in most places. I didn’t get it off of the filter basket holder yet. (click on photo to enlarge)

By getting the pH levels more under control, not only will I save the heater, but I will save money on chlorine tabs. At this point, big bags of baking soda from Costco are pretty inexpensive. It may have been a nice color purple, but I will be happy to only see it in swimming suits and beach towels around the pool from now on.